Distribution Process

Let's start with: What is a distribution?

Capital distributions are a common procedure in the financial world. Most capital distributions are payments related to assets from an account, fund, or individual security to investors or other beneficiaries, or those related to payments of stock or other payouts to shareholders.

The source for a distribution can be a number of financial products. Still, a distribution usually consists of a direct payment to a beneficiary.

As distributions are essential for financial products, especially securities, they have also found their way into the Polymesh design.

What we already covered in Origination:

- How the underlying asset has a lifecycle of its own, different from that of the security token. Typically expressed with the on-chain actions:

- Minting, a.k.a. issuance,

- Distributing, a.k.a. transfer;

- How the primary issuance agent (PIA) is in charge of minting the asset, and so of its total supply.

Now, how does it take place in practice?

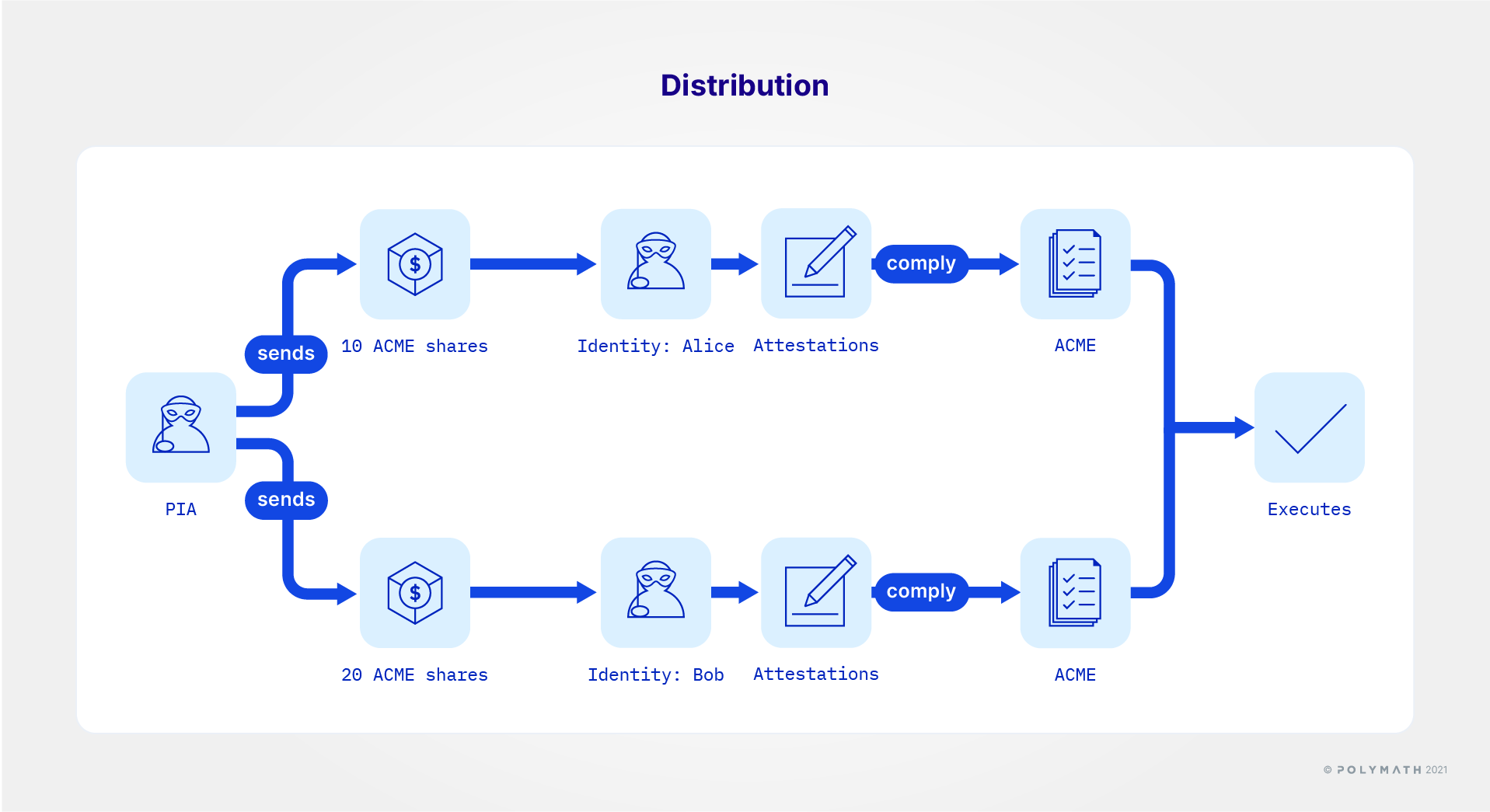

The owner of the token has delegated a large amount of trust to the PIA. The PIA issues to themselves the amount of shares that they have been tasked with distributing to the ultimate beneficiaries. With this action done, in one or multiple steps, they can proceed to the distribution.

As has been repeated many times, and will be later too, most actions on Polymesh carry consequences, and for this reason, targets and recipients need to accept actions too. This is no different for the recipient of a capital distribution. Each recipient needs to accept, and perhaps reject.

Atomicity

An important property of all blockchains is the indivisibility, or atomicity, of operations they enable. For instance, if the desired operation is to send 10 shares to Alice, then when Alice accepts, she receives her 10 shares. This is simple. It bears nonetheless repeating that "Alice receives 10 shares" was the indivisible operation.

A more complex example would be that the desired operation is:

- Alice receives 10 shares, and

- Bob receives 20 shares.

There is a missing part from this seemingly simple statement. What should happen if Alice rejects the operation? Does Bob still receive his shares, or should he be prevented from collecting them?

It is a matter of desired outcome, and the token owner, or the PIA, may have a preferred outcome. Perhaps, giving a veto to each party is a way to record the consensus of all parties about the shareholding structure.

For each desired outcome, there is a different way of structuring the distribution.

Instruction

The indivisible, or atomic, operation when distributing on Polymesh is called the instruction.

Therefore, if the PIA wants both Alice and Bob to receive their shares independently of the decision emanating from the other party, the PIA would have to structure the instructions the following way:

- Instruction 1: Alice receives 10 shares, independently from Instruction 2;

- Instruction 2: Bob receives 10 shares, independently from Instruction 1.

On the other hand, if the PIA wants both Alice and Bob to be in agreement for both, they would have to structure the instruction thus:

- Instruction:

- Alice receives 10 shares;

- Bob receives 10 shares.

For the avoidance of doubt, if both Alice and Bob approve the instruction, but one of them doesn't satisfy the compliance requirements of the token, the instruction doesn't execute yet, but remains in a pending state.

Asset checkpoints - Permanent records

During the life of a token, some actions require knowledge of the asset distribution - Who owns how much? Examples include capital distribution and corporate ballots. Moreover this knowledge typically needs to be collected for a specific point in time, and available now and later - Who owned how much on January 1st, 2021?

To achieve this, Polymesh implements a classic lazy-checkpointing mechanism. In effect, upon creation, the checkpoint only records:

- the date at which it was issued, and

- the total supply at the block height it was issued.

Note how "who owns how much" is missing from the record at creation. Since there is no limit to the number of investors, there would be no limit to the number of copy operations. Instead, to find out "how much did Alice own?", the system first looks into the checkpoint records for a value, and if missing that, picks Alice's balance now.

To make it possible, Polymesh keeps an eye out and will record in the checkpoint the previous balances of parties before any transfer between said parties, or any other action that changes balances for that matter.

For the avoidance of doubt, if there are no transactions after the checkpoint's creation, then it will not record any held balance as, indeed, the current blockchain data is the same as the desired data at the checkpoint.

One can create a checkpoint in two ways:

- create it immediately, or

- schedule future creation(s) at intervals.

Conclusion

We have seen the concepts that apply to the distribution of capital. Let's see how this looks in the Token Studio with the exercise coming up next.